Here’s how one company was able to scan large and very heavy parts from all four sides and from above, without having to laboriously move the piece. Article by ZEISS.

When a robot grasps a cylinder block weighing 50 kilos and approaches a saw or milling cutter, any vibration or sliding motion must be avoided. But deviations from target production data make it difficult for the robots to grasp. August Mössner GmbH & Co. KG, which manufactures specialised machinery for the foundry and aluminium industries along with saws for the widest possible variety of materials as well as equipment for the dismantling of nuclear power stations, has found a solution for this problem. As well as tailor-made manipulators for robots manufactured with the aid of the ZEISS T SCAN, the programming of the equipment is optimised with flexible laser scanning.

The two robot arms rigidly stretch their necks into the air, their movements appear frozen. One of them holds a cylinder block in suspension, weighing at least 50 kilos. Only in a few weeks’ time, when the entire plant has been completed, will they start moving and saw off disturbing feeder and sprue systems and mill off casting flashes on engine blocks coming from a foundry. To do this, they heave the parts to saws and milling machines that protrude from the wall and look like giant dentist drills.

Here at August Mössner in Eschach is not where they will be put to work, however, but rather at engine plants of well-known automobile manufacturers. The processing stations are designed and put into trial operation at August Mössner, which has a reputation in the automotive industry for delivering automated production lines with dozens of robots on schedule and perfectly functional.

Deviations of Several Millimetres

Christian Kunz is the Head of Robotics, R&D, at August Mössner. His team plays an important role when it comes to deviations. The 20 employees of his robotics, research and development department are responsible for planning the precise, safe and efficient operation of the processing lines.

But the devil is in the details. One of these details are the contour parts with which the robots grip the cylinder block. They are as small as a hockey puck, but must be able to grip the casting precisely and hold it in position during processing, against the forces that occur. For this purpose, the contour parts have recesses that fit exactly over the bulges of the castings. However, this is initially not the case.

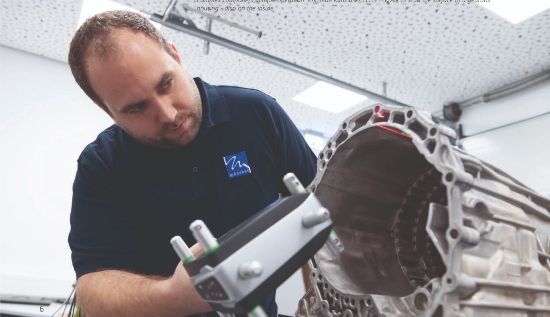

Kunz holds a contour part to the rough casting of a gearbox-housing, at the point where the robot is later to pick up the component. But no matter how the mechatronic engineer turns and tilts the fitting, the parts do not fit together. “When car manufacturers send us castings, they often deviate from the target design by a few millimetres,” explains Kunz.

This is no wonder, since most of them are so-called start-up parts for new engine types.

The tolerances are still large when series production starts and are not shown in the CAD models of the castings. Kunz and his team have found a solution in which ZEISS T-SCAN is of central importance. Using a hand-held laser scanner, the engineers measure the surface contour of the casting—for example, of an engine block or a transmission housing—and compare the data set generated by this with the target CAD data supplied by the car manufacturer. On the one hand, this serves to document the actual state and on the other hand, the measurement is the basis for adapting the contour parts to the casting and for subsequent programming of the robot. In this way, the engineers can quickly see where there are deviations and can immediately initiate reworking of the contour parts. The contour part is reworked by hand, then scanned and can thus be documented and converted into CAD data.

Еще больше новостей |